Increasing cassava production and developing the technology for cassava processing involve tackling problems in such areas as technology, productivity, marketing price stability, and production continuity. Once harvested, cassava is perishable, that is, the roots are of acceptable quality for only a few days, creating a major problem for farmers who are thus in a low bargaining position. Cassava flour is one way of overcoming this problem.

This study aims to (1) develop the cassava flour industry at three levels, (2) increase cassava’s added value and thus farmer income, and (3) develop this industry in rural areas.

Three levels of development of the cassava flour industry were attempted in rural areas. The first was at the level of the individual farmer, where farmers’ activities included cassava flour production, marketing of cassava flour, and processing and marketing flour-based products. The second was at the farmer group level, where farmers worked together to produce cassava flour, market it, and process and market flour-based products. The third was at the cooperative level, where the cooperative village unit (Koperasi Unit Desa) collects cassava flour from farmers and farmer groups, and then sells it to the retail trade and food industry, the feed industry, and other consumers.

Results indicated that marketing was a major problem in Central Java’s cassava flour industry. Cassava flour use and its processing technology have not yet developed. The cassava flour industry has little knowledge of and experience with marketing, which hinders development. The industry can be developed in rural areas only through the cooperative system, or the farmer group system, if given support in developing processing technology and household industry, and in obtaining processing equipment and machinery.

Introduction

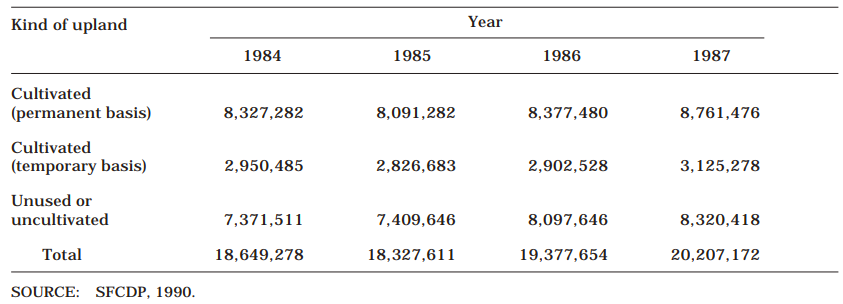

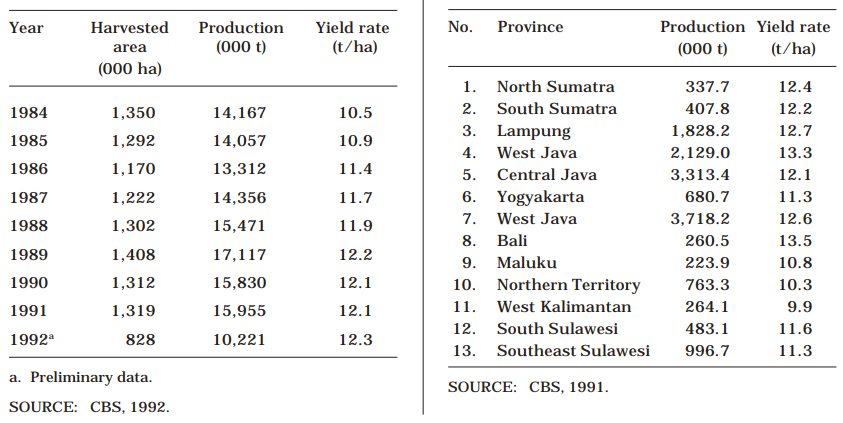

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is the most important staple food crop after rice and maize in Indonesia. At present, farmers cultivate cassava in almost all areas of Indonesia, from lowlands to highlands, in dry or wet climates, and under various soil conditions. Table 1 summarizes the use of upland areas in Indonesia. Wargiono (1988) stated that the harvested area of cassava in Indonesia showed a decreasing trend of 0.7% per year. But since 1986, the trend has increased slightly and, in 1991, the total harvested area was about 1.3 million hectares, with a total production of almost 16 million tons (Table 2). Cassava’s production rate from 1969 to 1985 was 2.05% per year (Affandi, 1986).

Thirteen of Indonesia’s provinces (Table 3) are major cassava-producing areas, each province having more than 10,000 ha under cassava (Pabindru, 1989). The average yield per ha is low at 10-12 t/ha. This can be increased by introducing new technologies to farmers such as improved varieties and cultural practices. On a cassava estate owned by a tapioca factory in Lampung, yields of 25-30 t/ha have been continuously achieved (Rusastra, 1988).

Problems of Developing the Cassava Agroindustry

These are cassava’s association with low social status; inadequate marketing, postharvest handling, processing, and cultural practices; and low productivity.

Association with social status

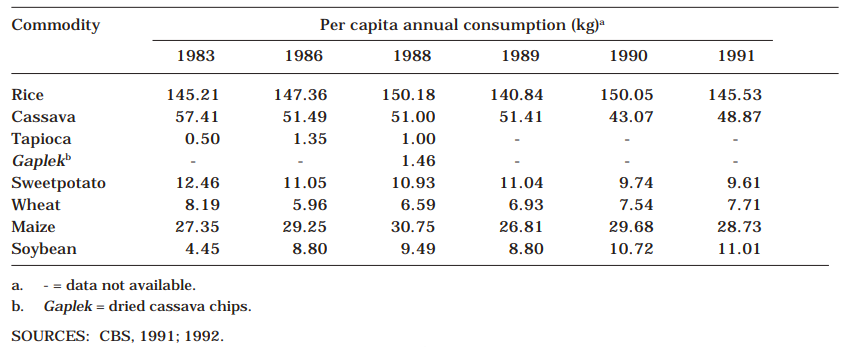

Most Indonesians consider cassava as a food for those of low socioeconomic status. When income increases, then consumers switch from cassava to rice. Cassava consumption per capita per year has tended to decrease gradually in Indonesia, dropping from 57.4 kg per capita in 1983, through 51.0 kg per capita in 1988, to 43.1 kg per capita in 1990 (Table 4).

Marketing

Most cassava in Java is used for human consumption or starch (tapioca). Cassava farmers near starch factories usually sell fresh roots directly to the factories, while those in remote areas tend to first process cassava into gaplek, or dried cassava chips, and then sell to middlemen, who transport and sell the chips to exporters or pelleting factories in urban areas. Farmers in Java sell about 50% to 90% of their fresh cassava roots to traders or middlemen.

Farmgate prices of cassava fluctuate between Rp (rupiahs) 26 and Rp 177/kg, according to location and harvesting time (Tjahjadi, 1989). Cassava is also perishable, and often cannot be processed or consumed immediately after harvest. These problems limit the flexibility of cassava and force farmers into a low bargaining position.

Postharvest handling and processing

Cassava is usually harvested manually, and may suffer severe damage if the roots are not carefully dug out of the ground. Roots deteriorate rapidly after harvest, and are bulky, making transportation difficult and expensive.

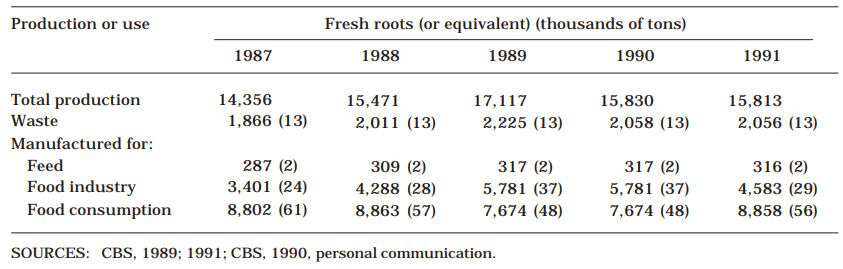

According to the Indonesian food balance sheet data (CBS, 1992), total cassava production in 1991 was 15.8 million tons (Table 5). Of this, 56.0% was consumed fresh or as gaplek; 15.7% was exported as gaplek (chips), pellets, and tapioca; and 20.3% was used as raw material in industries such as tapioca (starch) (7.9%) manufacture and nonfood industries (12.4%). Postharvest losses are relatively high, about 13.0%.

Cassava roots can be used in various forms: fresh roots are cooked (boiled, roasted, steamed, or fried); fermented to produce tape; dried (either whole root, slices, or chips) to produce gaplek; extracted to produce tapioca (starch); or the gaplek milled to produce flour. Gaplek can be kept as a food reserve or as animal feed. In villages of Java, most cassava is used for human consumption, and many traditional products are produced for local and national consumption.

Cassava as a marginal crop

Farmers tend to grow cassava with traditional, sometimes inadequate, technology. Being a crop with unstable prices (a consequence of undeveloped processing technology), cassava is often grown in fragile soils with little or no investment in fertilization.

Study Objectives

Our study aimed to (1) improve postharvest handling of cassava by farmers, (2) introduce and develop cassava flour production and the processing of flour into other products, and (3) develop household and small-scale cassava processing industries in a village of Central Java.

Materials and Methods

Research took place in Kejobong Subdistrict, Purbalingga District, Central Java Province, during 1991-1993. It was conducted in three phases: surveying, introducing cassava flour production and processing technology, and evaluating the development of the cassava flour industry.

Surveying cassava postharvest handling and processing

A survey was carried out in Purbalingga District, from May to June 1991. Primary data was collected from farmers on how they handled cassava after harvest, processed the roots, and marketed their products. A literature search was also conducted on cassava production, area of land use, and cassava processing in Purbalingga District. From all these data, we chose the experimental site.

Introducing cassava flour production and processing technology

The second phase, that of introducing new cassava flour production technology and processing, was conducted from August 1991 to March 1992.

Evaluating the development of the cassava flour industry

The development of the cassava flour industry in Kejobong Subdistrict was evaluated during June to September 1993. The evaluations were at individual, group, and cooperative levels in rural areas, including cassava flour entrepreneurs. Production, processing, marketing, and other problems were also assessed.

Results and Discussion

Survey results

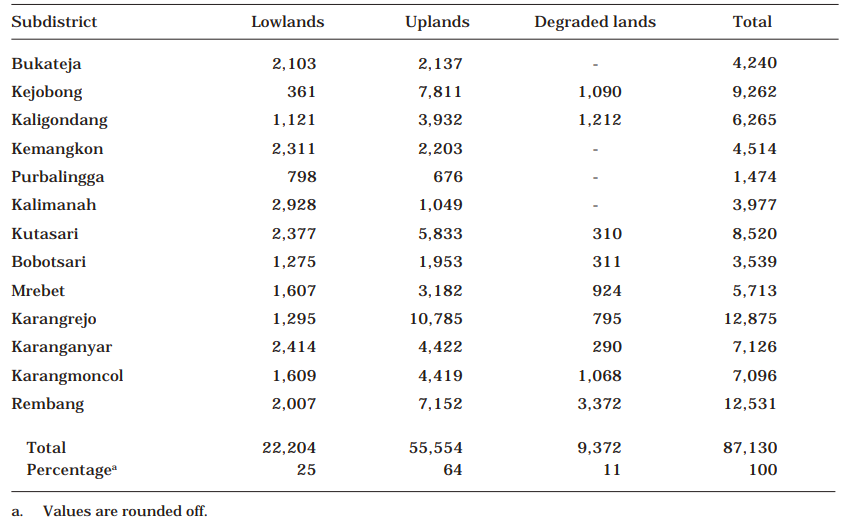

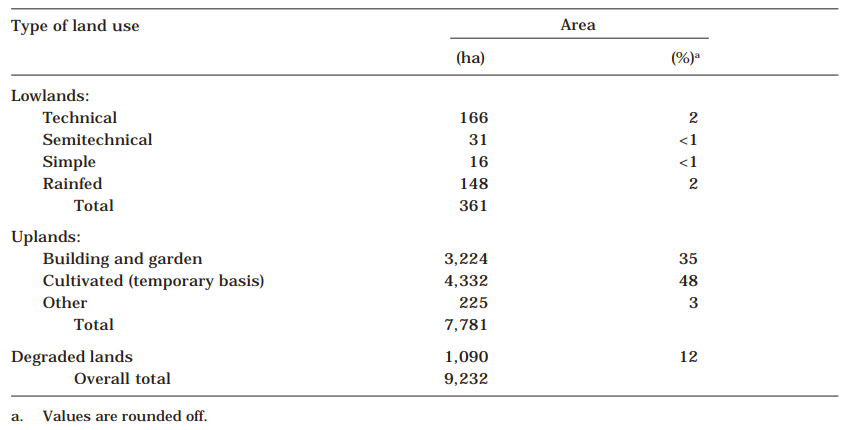

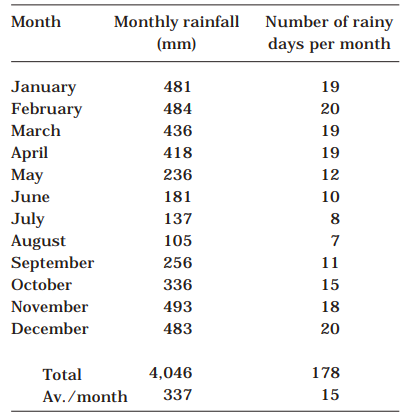

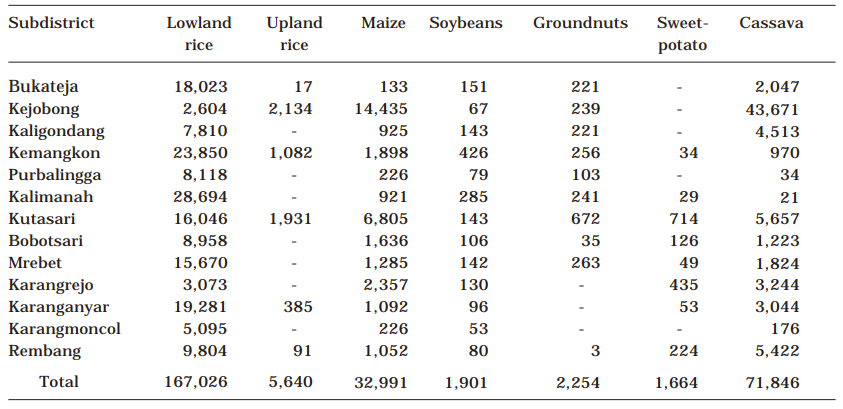

Socioeconomic conditions of Kejobong Subdistrict. Table 6 summarizes land use in Purbalingga District. Land use in Kejobong Subdistrict is divided as uplands (about 84%), lowlands (4%), and degraded lands (12%) (Table 7). Altitudes range from 70 to 100 m above sea level, climate is type A, and annual rainfall is 4,048 mm (Table 8).

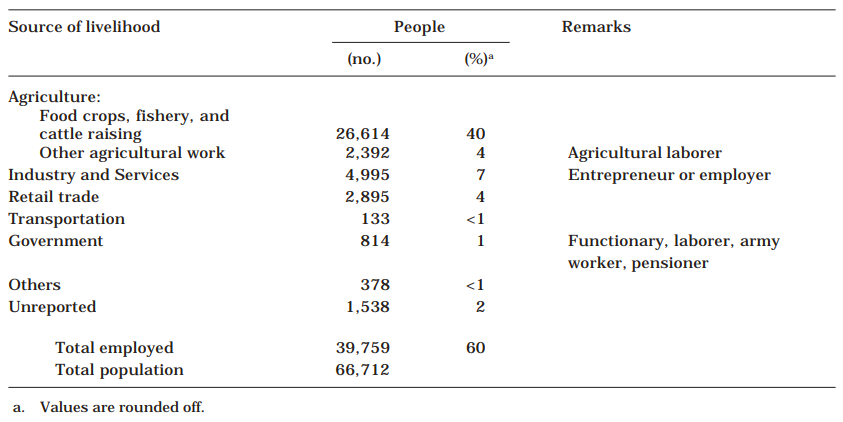

Total population in Kejobong Subdistrict was 66,712 (32,622 males and 34,049 females). Most people in Kejobong derived their income from agriculture: 40% from food crops, fishery, and cattle raising; and 4% from other agricultural work. The rest worked in industry (7%); retail (4%); transport (<1%); government (1%); and others (<1%). About 2% of employed were not reported (Table 9).

Kejobong is the major center of cassava production in Purbalingga District. Production was 43,671 t in 1986 (Table 10).

Harvesting, and postharvest handling and processing

Harvesting. Two major varieties of cassava are planted in Kejobong: the bitter ‘Klanting’ (90%) and the sweet ‘Darme’ (10%). Harvesting is usually by hand during August to November. Of 36 respondents in seven villages, 7 harvested the cassava themselves, 6 paid others to harvest, 4 harvested through the cooperative system, 17 had sold the harvest in advance, and 2 did not harvest.

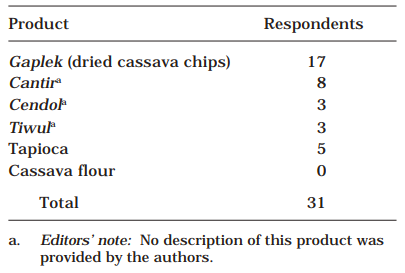

Postharvest handling and processing. Postharvest handling and processing of cassava have not yet developed in Kejobong, because most farmers sell cassava as fresh roots. Only about 30% of farmers process cassava, producing such traditional goods as gaplek, tiwul, and cantir. Only 5% of farmer-processors produced tapioca (Table 11).

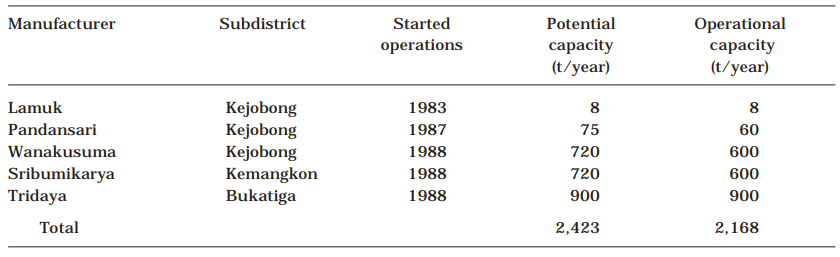

The farmers either sold peeled cassava to middlemen (50%) and retailers (8%), or were paid in advance before harvest (42%). Because the total potential capacity of factories was equivalent to 12,092 t of fresh cassava (i.e., 2,423 t of tapioca) (Table 12), the total cassava production of 71,846 t could not be processed. Consequently, cassava prices fell, fluctuating according to retailer or tapioca factory. In 1989, the price of cassava ranged from Rp 25 to Rp 30/kg.

But after cassava flour processing was introduced, the price of cassava rose from Rp 50-60/kg in 1990 to a peak in 1991 and 1992 at Rp 90-115, and dropped slightly to Rp 70-80 in 1993. Two years ago (i.e., 1991/92), the production of cassava flour was not profitable, because the cassava flour price ranged from Rp 350 to Rp 400/kg.

Cassava flour production involves several processing steps: peeling, washing, slicing or rasping or chipping, pressing, drying, and milling (Figure 1). These new technologies were introduced, by demonstration, to farmers, farmer groups, and members of the Village Unit Cooperative, or Koperasi Unit Desa (KUD). These people assessed the technologies and were then trained in their use. Cassava flour is used to substitute wheat flour in the making of such foods as pancakes, cookies, cheese sticks, and putu ayu.

The cassava flour industry was developed in rural areas as a three-level system (Figure 2). On the first level, the individual farmer produced cassava flour, and processed and marketed it himself. On the second level, the farmer group performed these activities. On the third level, the KUD not only produced cassava flour, but also received it from farmers or farmer groups, and then sold it to food industries and middlemen.

Cassava Flour Production and Processing Development

The objectives of this development project were to (1) encourage the production and processing of cassava flour by individual farmers and farmer groups, and (2) increase the added value of fresh cassava by processing it into flour. The project was conducted in three phases.

Introducing cassava processing equipment

Processing equipment was demonstrated to farmers to arouse interest in cassava flour production, encourage an increased working capacity and product quality, and promote the development and manufacture of processing equipment in rural areas. The equipment introduced and demonstrated included slicers, carvers, graters, and presses.

The Kejobong KUD, in particular, received, from the Government, equipment with a daily capacity to process 10 t of cassava roots into flour.

Cassava flour production

Flour production would help sell cassava when prices are low and demand from tapioca factories is also small.

In 1992, individual farmers produced about 300 kg of cassava flour, which was processed to cookies and pancakes. Farmer groups produced 1 t of cassava flour and cooperatives 5 t. They sold it to food industries and middlemen. The major problems of cassava flour production at all three levels were found in marketing.

Food technology and cassava flour use

Marketing and food technology are important in the successful development of a cassava flour industry. Successful marketing is influenced by product utility and requisites for quantity and quality. Developments in food technology increases opportunities for marketing cassava flour. Outlets for the flour are food, chemical, and other industries, household consumption, and traders (middlemen, retailers, and exporters). Such developments in food marketing and technology have yet to arrive in Kebojong Subdistrict.

Assessing the Development of the Cassava Flour Agroindustry

Developing the cassava flour agroindustry in rural areas was expected to extend cassava marketing and agroindustrial development in rural areas, and to increase farmers’ income. The project was evaluated from May to September 1992.

The price of fresh cassava during May and June 1993 in Kejobong ranged from Rp 50 to Rp 60/kg, and that of cassava flour ranged from Rp 250 to Rp 350/kg. In May and June 1992, the typical farmer produced 200 kg of cassava flour, selling it to food industries. The typical farmer group produced 500 kg of cassava flour, selling it to feed industries. The KUD, however, did not produce cassava flour, not finding it profitable.

The price of cassava roots increased from Rp 70-90/kg in August-October 1993 to Rp 95-105/kg in November 1993. Farmers and farmer groups therefore found cassava flour production unprofitable. Other farmers used cassava for feed and food. The typical farmer would use 5-10 kg/day of dried cassava to feed sheep and 40-50 kg/day for cantir production.

The problem

Despite the low prices (Rp 50 to Rp 60/kg) farmers said they had no problem marketing cassava roots. In contrast, producers explained they had problems marketing cassava flour because it is a new product for which food processing technology has not yet been developed, and of which few consumers know much about.

Summary

- Farmers, farmer groups, and KUDs had no experience in marketing cassava flour.

- Processors and consumers lacked information on cassava processing technology and flour use.

- Appropriate cassava flour processing technology must be developed if the cassava flour industry is to develop in rural areas.

- Further research is needed on cassava flour use.